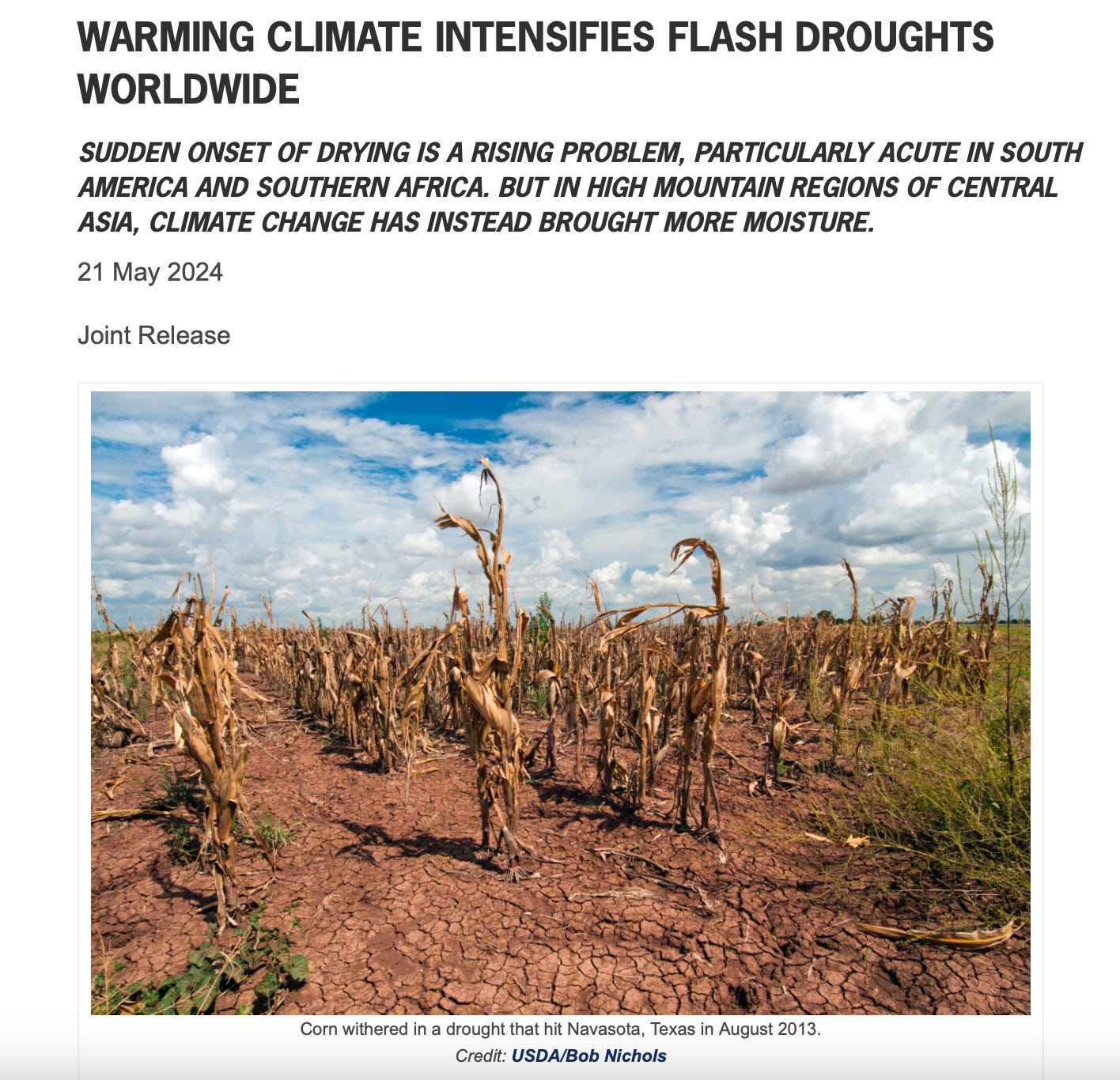

In this ‘lean period,’ as John Wright describes July in The Forager’s Calendar, I've been thinking about famine foods, especially as the subject intersects with the reading I’m doing around climate change, its impact on agriculture and on our abilities to feed ourselves. Increases in global heat is causing crop failures, reduced yields, damaged harvests by flooding and flash droughts. Last year India started to ban exports of rice because of potential shortages. Threats caused by unpredictable weather especially in countries that are already experiencing effects of warming are being exploited by big corporations who have been raising prices. This is, in turn, causing more food insecurity, felt acutely by poorer nations and those in socio-economically disadvantaged people in wealthier nations.

Despite the severity of the situation and likelihood of food insecurity becoming far worse in the coming years and decades, I am discovering that very little research has been done around famine foods. In an online talk around his 2021 book Famine Foods: Plants We Eat to Survive, anthropologist, archaeologist and ethnobotanist Professor Paul Minnis, stated that if you search on Amazon for books on the cultural side of food as well as texts on various national cuisines, thousands of entries are returned. But when you go back to basics of how we need food to keep us alive, there are very few resources. We wouldn’t exist if our ancestors hadn’t eaten famine foods. This under researched area should be a critically important part of our cultural heritage but sadly so much of the knowledge has been lost over the generations. Minnis comments although we spend huge amounts of time and resources to preserve germplasm in seed banks, we should also be safeguarding the memory of the kinds of plants, fungi, algae etc. to eat and how to prepare them, when there isn’t anything else to feed ourselves.

Unsurprisingly, our governments are grossly unprepared for what is likely coming down the line, but it hasn’t always been the case. In historical periods of food insecurity and famine, leaders have supported their populations with information. The Dutch government during the “Hunger Winter” famine of 1944-45 published instructions of how to carefully prepare tulips bulbs as well as “illustrated folders” on how to identify and prepare wild edible plants and fungi. In the UK, the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries distributed booklets of edible and poisonous fungi with various editions and reprints from 1910 until 1950. During and after the Second World War, they produced ‘Hedgerow Harvests’ pamphlets which for example encouraged rosehip collection and processing as syrup to supplement the lack of vitamin C caused by the reduction in imported citrus.

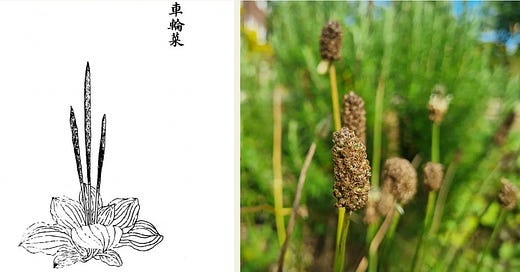

One of the oldest written compendiums of foods for difficult times is from China, Jiuhuang bencao, which might roughly translate as ‘Treatise on Wild Food Plants for Use in Emergencies’ (Needham, Lu, Huang, 1986) likely written by the Ming dynasty prince Chu Su in 1403-06. The famine herbal which outlines over 400 plants that could be used as food and medicine in hard times was researched by cultivating them in “famine gardens” (Plunkett, 1991: 7, citing Christopher, 1985). There were also woodcut illustrations made, one being of broadleaf plantain / Plantago major. I have been collecting the seedheads of the ribwort variety this month making them into tasty crackers.

I got serious about foraging at the start of the Covid lockdowns in spring of 2020. At that point despite panic buying occuring in the UK, we weren’t in a famine situation, but access to food in shops became dangerous. I sought more food security and self-sufficiency to reduce the threat of infection by minimising trips to the supermarket. Desperate to eat fresh greens, I attempted growing chard and other vegetables, but was also compelled to learn about which of the weeds in my garden and the wild plants in my local environment were edible and what they might offer by way of nutrition. And so my love affair with foraging began.

It was dandelion, sow’s thistle, sheep’s sorrel, fat hen, plantain and ox eye daisy that I first confidently identified in the garden, I learnt of garlic mustard on my local riverside walk and wild garlic in a local wood. I also discovered that as well as the fruits that I had made into jellies the previous autumn, I could also eat hawthorn leaves and blossom.

During my research into edible wild plants and fungi, I have recently been trying to collect mentions of what might have been eaten during times of hunger. Robin Harford of Eatweeds in an audio essay (which is no longer available) identifies that in "some regions [haws] were viewed as famine food [...] In World War II, the fruit became an ingredient in bread, echoing an earlier Irish tradition where it was known as poor man’s flour”. Harford also mentions in that hazel catkins had once been ground into flour in Slovakia in the beginning of the nineteenth century.

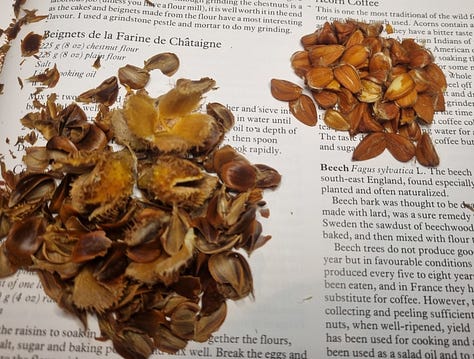

In November last year I was gathering beech nuts, which have been used as a famine food. In the winter of 2022, I also experimented with making acorns into flour which according to FoodPrint’s Real Food Encyclopedia, was “a major food staple” for “ancient Greeks, Iberians, Japanese and English” who practiced balanophagy i.e. eating acones, “especially during times of famine when grains were unavailable” by leeching out the tannins (FoodPrint, 2024). And in December, I also discovered the cambian layer, the soft, white inner bark of pine trees which is often used to make flour by the Sami people in times of hunger and scarcity.

In The Wilderness Cure, where she documents a year eating only wild foods with the inevitable periods of hunger and scarcity, Mo Wilde reflects when foraging around her local Ikea car park, that it is “the “tough guys” [that] are the first to arrive on broken land: nettles, thistles, docks and willowherbs, as well as the opportunists: mustards and cresses. As if they somehow know that desecration of the landmarks the poverty of people, all these plants also provide a rich food bank of nutritional values and medicinal powers. Nettle tops, thistle roots and stems, willowherb shoots, bittercress rosettes: these are foods for the hungry and there for the taking. Free for all” (Wilde, 2022:100).

As well as the ‘lean period’ at this point in summer that Wright describes, Wilde identifies Earrach, the Celtic spring, commencing when January gives into February. It is, she writes, “the hungry gap, the Lenten period when winter supplies are running low but domesticated fruits and vegetables have yet to sprout. However, many wild plants do grow throughout this period. They enjoy the lack of competition from the grasses, butter-cups and nettles and quickly flourish to have their day in the sun” (p.76).

At this point, I paused and asked those who had joined the Commons Feast the following questions to kick off our discussions:

Do you know of any wild foods that were eaten during times of hardship?

What foods would you consider as famine foods? And what would be your go-to foods during scarcity?

References:

FoodPrint (2024) ‘Real Food Encyclopedia: Acorns’. At: https://foodprint.org/real-food/acorns/#:~:text=For%20many%20cultures'%20ancestors%2C%20the,famine%20when%20grains%20were%20unavailable(Accessed 12/07/2024).

Frequently Found Growing on Disturbed Ground (2011) ‘Balanophagy for Beginners’ 04/11/2011. At: https://ondisturbedground.wordpress.com/2011/11/04/balanophagy-for-beginners/ (Accessed 13/07/2024).

Ghosal, A. and Musambi, E. (2023) ‘A rice shortage is sending prices soaring across the world. And things could get worse’ In: The Associated Press 22/08/23. At: https://apnews.com/article/rice-prices-shortage-india-ban-a7364dbdb6fd04934090bd2943e24bbd (Accessed 12/07/2024).

Harford, R. (2024) ‘Hazel’ In: Eatweeds. At: https://www.eatweeds.co.uk/hazel-corylus-avellana (Accessed 13/07/2024).

Lester, L. (2024) ‘Warming Climate Intensifies Flash Droughts Worldwide’ In: AGU 21/05/2024. At: https://news.agu.org/press-release/warming-climate-intensifies-flash-droughts-worldwide/ (Accessed 12/07/2024).

Minnis, P. E. (2021) Famine Foods: Plants We Eat to Survive. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press.

Minnis, P. and Turner, N. (2021) Famine Foods: Plants We Eat to Survive [Online talk] The University of Arizona Press 06/05/2021. At:

(Accessed 12/07/2024).

Needham, J., Lu, G., Huang, H-T. (1986) Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 6 Biology and Biological Technology, Part 1: Botany. Cambridge University Press.

Plucknett, D. L. (1991) ‘Saving Lives Through Agricultural Research’ In: Issues in Agriculture (1) Washington D.C.: Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research, CGIAR. At: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/132696115.pdf (Accessed 19/07/2024).

Vorstenbosch, T., de Zwarte, I., Duistermaat, L., and van Andel, T. (2017) ‘Famine food of vegetal origin consumed in the Netherlands during World War II’ In: Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 13 (1) 63. At: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0190-7 (Accessed 17/11/2023).

Wilde, M. (2022) The Wilderness Cure. London: Simon & Schuster.

Have you seen how many store food during the war too, and even now it’s being used in areas where seasons dictate the amount of food available such as canning, and storing meat in jars and eggs in lime and such