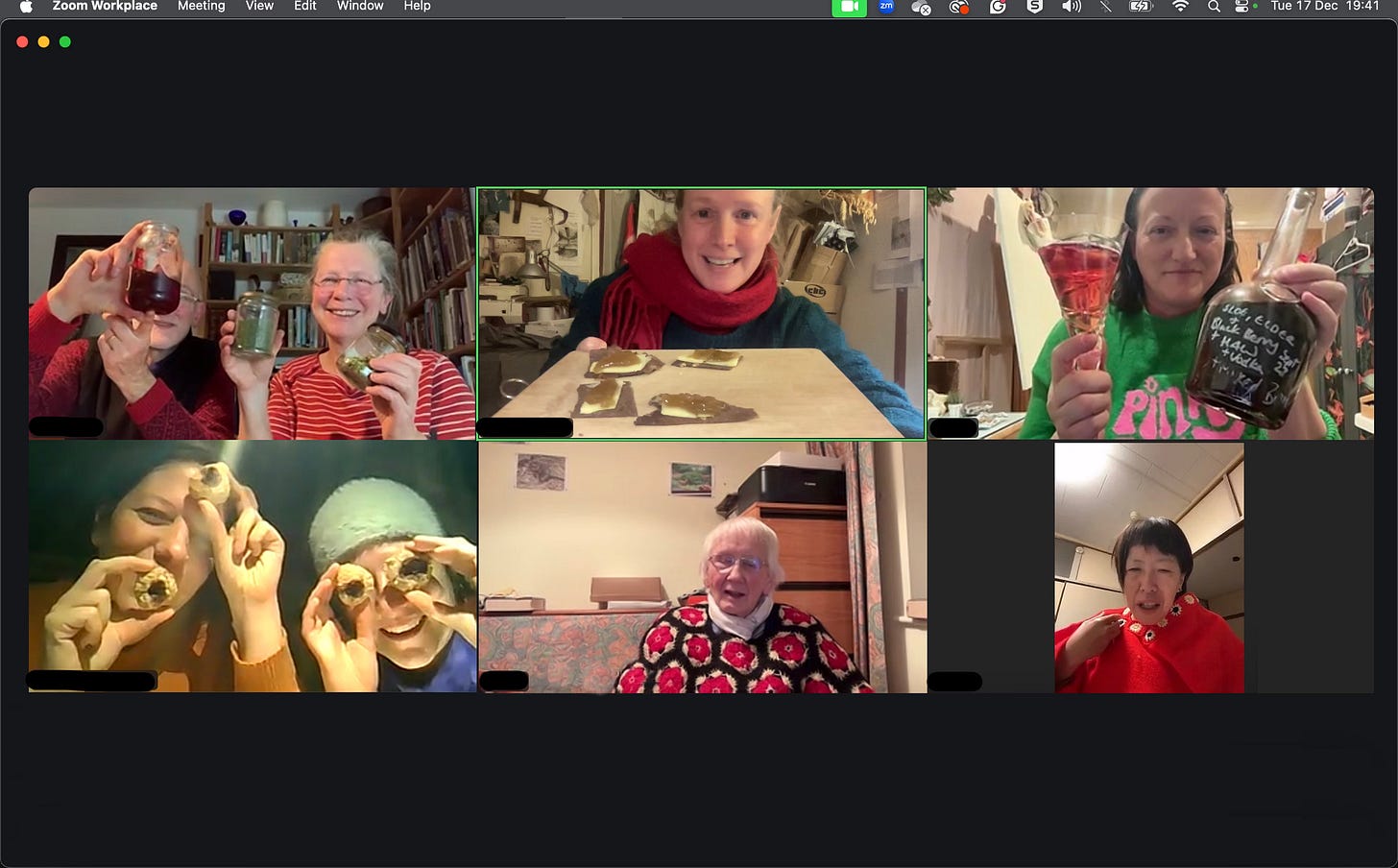

We had a lovely gathering of eleven for December's Commons Feast calling in from a variety of geographical locations and time zones. In Japan, a participant was joining at 4 am and another at 1.30 am in Sri Lanka! Slightly closer to home, we had participants from Germany and Italy. From the UK, we were joined by people from London, East Sussex, and Devon. Although connecting from Scotland, a pair of guests had recently returned from the Netherlands where they are also resident, bringing Dutch perspectives on the subject of spices.

During my introduction, I managed to confuse everyone with my mispronunciation of wood avens, which I learnt is pronounced 'avons' (like the river) rather than 'aveens'! So once everyone understood what I was talking about, we had a lovely discussion where many recognised the plant in their gardens, verges and/or edges of woods, but hadn’t yet tried pulling up and using their roots.

Hogweed seed, a UK native spice with a flavour profile akin to allspice, bitter orange and cardamon, however, had been collected recently. The couple calling in from Scotland talked of it being known in Persian cuisine as golpar being combined with sesame and used in savoury as well as sweeter recipes. They have been picking hogweed from their garden, preferring the seeds when they are still green, which they dry and eat as snacks. This was also the first year that they had started eating its young shoots and leaves, just as they began to unfurl, and have already found it one of their favourites. They are confident with gathering from the carrot family — as they had been on a foraging course— learning how to distinguish common hogweed from some of the most toxic plants in the family, hemlock water dropwort, hemlock, and the imported giant hogweed, Heracleum mantegazzianum. They also learnt how to pick common hogweed safely wearing gloves, as its sap can cause allergic reactions if you get it on your skin, but not anywhere near as severe as the burns that giant hogweed sap can cause with lasting phototoxicity.

Magnolia flowers have also been identified as part of the UK’s spice rack, offering a ginger-like zing to dishes. Some participants have been pickling the buds in apple cider vinegar, rice wine vinegar and picking spices, as well as eating them raw in salads, noting that different trees develop different flavours. I have also learnt that petals can also be dried and ground to preserve their flavours beyond early spring. Nasturtium flowers and leaves were offered as alternatives to pepper.

Our participant calling in from Sri Lanka spoke of the clove tree, Syzygium aromaticum in their garden, and the harvesting of the buds which usually begins in December. There, it is used in almost every meal but also prized for its medicinal qualities, particularly for its anaesthetic properties for toothache where a clove would be bitten down on, rather than the oil being used as it is felt to be too strong. It is also employed as an insect repellent, to prevent termites, to keep moths at bay in clothing cupboards, and a couple of cloves placed in sugar deters ants.

The legacy of the colonial spice trade was shared and experienced by participants who had been in the Netherlands earlier in the month on 6 December for Saint Nicholas or Sinterklaas celebrations. As well as processions there were lots of feasting with traditional foods falling into what were described as two different categories: one heavily spiced with cloves, cinnamon, mace and nutmeg, for example, a clear vestige from the activities of the Dutch East India Company or as it is called in Dutch, Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, and the other much more plain foods such as potatoes, sauerkraut etc.

We learnt of a German Christmas macaroon from a pair of sisters joining from their family home in Germany for the holidays. The dough, made with oats and ground nuts is shaped on a baking tray and a thumb-sized hollow is then laked with jam made from blackberries earlier in the season. I proposed that preserving and then eating foods from previous seasons enables us to stretch or fold time. This was quite apparent for one participant who discovered a liqueur in the back of the cupboard infused with haws, blackberries, elderberries and sloes, that had been forgotten, transporting the tastes of a previous season to the present. This participant commented on the unseasonably warm weather that we have been having in the south-east of England that has recently triggered spring shoots to sprout such as cleavers, and three-cornered leek. Whereas those in Scotland were eating an Italian-style stew made from nettles preserved in the freezer, dried nettle and hogweed seeds, mixed with a tin of beans, tomatoes and chillies.

Medlars were shared from Italy, and a discussion ensued about the process of bletting and preserving as others also had experience with this. Despite their success last year, one participant tried three times unsuccessfully this season to get their medlar jelly to set. The participant from Italy prefers to bake them in the oven stuffed with almonds and raisins to add flavour. She also gave a tip on the freezing of parasol mushrooms which was to freeze them raw not cooked, which delighted our regular participant from Devon who had been disappointed last month by her batch of frozen parasols that had been put in the freezer after cooking that hadn’t fared well.

For my dishes, I used Douglas fir needles to spice up a fruit jelly with citrusy notes that I paired with some strong cheddar on top of dock seed crackers. Fruit cheese paste traditionally made with quince in Spain, is known as Membrillo. It is a very thick jelly-like way to preserve fruit. Some of us shared the challenges we had making it. Mine hasn’t quite set enough, and another’s set too hard. My dock seed crackers were also flavoured with dried and ground blackberries saved from a gin infusion. I also made Parkin, a heavily spiced cake from Yorkshire, for the first time. Mine was spiced with ground ginger, hogweed seeds and wood avens syrup.

The session became a bit of a recipe share where many of us talked of specific dishes as well as desires to receive more in-depth methods and ingredient lists for all of the foods that we were talking about which reminded me of what commoner, food researcher and anti-hunger activist, Jose Luis Vivero Pol write in ‘Food as a commons: Reframing the narrative of the food system’. The exchange of recipes in “almost every culture” is “a superb example of commons in action” (Walljasper, 2011 in Vivero Pol, 2013: 16). Despite the commercialisation and commodification of our industrial food system, there are still “several dimensions of food production and consumption [that] are yet considered as commons” and “cooking recipes” is one of them. (Vivero Pol, 2013: 5). So in the next couple of weeks, I will set about gathering and sharing these recipes.

References:

Vivero Pol, Jose Luis, Food as a Commons: Reframing the Narrative of the Food System (April 23, 2013). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2255447 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2255447